Often, we’ve gotten too far into our media consumption to examine the exact food we’re offered, too satisfied with the fast delivery to question the recipe or origin. The NBA offseason might be the worst offender.

A beautifully humanizing moment, like R.J. Barrett and his father realizing a lifelong dream together, had maybe eight hours of spotlight before Barrett stepped on the court and into the nonsensical take chamber of our sports media.

Step back a few paces and you’ll see a legion of NBA fans insulting the performance of a teenager at essentially his summer internship, grown men and women putting an expectation of maturity and assuredness on nineteen-year olds that they’d revolt against if their parents did the same. If you checked my stats at 19, you’d find shockingly low college assignments done per day and a somewhat impressive kill/death ratio in Halo 3.

Barrett, Zion, and his colleagues may have known that accepting a spot in the NBA required them to give implicit permission for strangers to nitpick and critique, but their silent allowance of something to happen does not prove that that action is worthwhile.

Barrett surely struggled in his early Vegas games, but Summer League performance rarely if ever serves as an indicator of future success. DraftExpress wrote a fantastic article explaining the weak correlation between top performers in this rough draft of a season against actual NBA production, showing minimal connection between the counting stats in Vegas against what a player might do in the regular season. Even my favorite duo on ESPN, Bomani Jones and Pablo Torre, fell victim to the easy downward punch, albeit with a more measured approach.

No one calls Barrett’s inefficient start ideal, but dismissing the 19 year old prospect so quickly makes no sense. Ian Bagley covers this middle ground perfectly in a conversation with NBA scouts about Barrett’s slow start, and the very same guy who couldn’t buy a bucket in his first two games ended play with two strong outings; Barrett went from bust to savior in under a week.

The NBA’s Summer League should be about celebrating and cultivating hype, not diminishing it, and while we can critique, do so knowing that these productions obscure far more than they reveal. In fact, we only have to look one year back to remember Kevin Knox, a player with the exact opposite experience to Barrett in his debut.

Knox starred in the summer and fell apart in the season

Kevin Knox joined the Summer League first team after a breakout series of performances, lighting Vegas up for over 21 points a game and convincing Knicks fans that he’d soon outperform his draft position.

Instead, he failed to find his footing in a tough rookie year. Per Basketball Reference, among all rookies since 2000 with similar workloads (at least 28 minutes per game and 20% usage), Knox had the single worst box score plus/minus and joined Collin Sexton, Dennis Smith, Adam Morrison, and Emmanuel Mudiay as the only players to post negative win shares. This effectively means that having Knox on the court actively cost his team a chance at victory.

Cleaning the Glass’s excellent stats database provides a variety of nuanced metrics that help understand how a player performs relative to his peers, and I wanted to use these metrics to help understand how Knox performed and where he could look to improve.

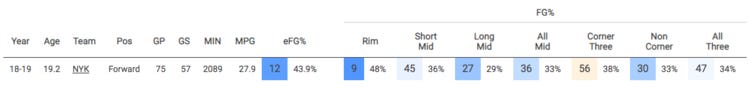

Knox had the unfortunate combination of taking inefficient shots and making them at a lower than average rate. Fourteen percent of his shots came in the midrange (80th percentile in the league for 2018-19) but only made 29% of them (27th percentile). His scoring at the rim dipped even further, making a nearly league-worst 48% his shots there. CLG helpfully breaks out each region and Knox's rank relative to his peers, and the bright blue unfortunately shows where he's well below league-average.

A recap of the lost season

To be fair to the young player, having two of his main point guards as similarly poor producers surely did not help Knox’s development. We’ve looked at the effect of a tank on rookie production before, and found no meaningful correlation between losing and not developing rookies, but these ruinous seasons certainly do not empower the players stuck on the tanking squads.

The Knicks offered a flimsy support structure for the young wing, ending the year with seventeen wins, twice as many gross headlines, and excitement mostly in the form of their bouncy block monster, Mitchell Robinson. While a tank does not necessarily kill any form of development, Knox surely felt the impact of playing without an established playmaker at point guard.

His playmakers often let him down. Per Cleaning the Glass, Emmanuel Mudiay ran point for the majority of the season, and while he did manage to raise the team’s effective field goal percentage by 1% while on the court, the team still posted an abysmal 49.5% field goal rate while he ran the show.

Any Knick fan with the constitution strong enough to watch last season’s tank saw Mudiay’s proficiency in the midrange, but his ineffectual, meandering drives to the hoop did little to open the corner threes for the team. Mudiay posted a bottom 25th percentile assist to usage ratio (Cleaning the Glass's stat that is essentially a measure of how often a player used his possessions to empower his teammates to score), and his late season counterpart Dennis Smith Jr did not improve the playmaking by much. While closer to league average in assist to usage, Smith still ran an offense with a 47.6% effective field goal rate, worse than Mudiay and good for the 3rd percentile in the entire league; an abysmal Knicks offense destroys everyone.

One glimmer of hope for the DSJ/Knox combo? A shared affinity for producing high value looks in the corner. DSJ improved the Knicks corner three accuracy by 5.3%–81st percentile in the league for playmakers–while Knox did his best work shooting from that area. He did only manage to hit league-average efficiency in that region, but for a broadly inefficient player, any steps toward the middle of the road represent improvement and hope.

While not KD or Kyrie, free agency may help Knox out

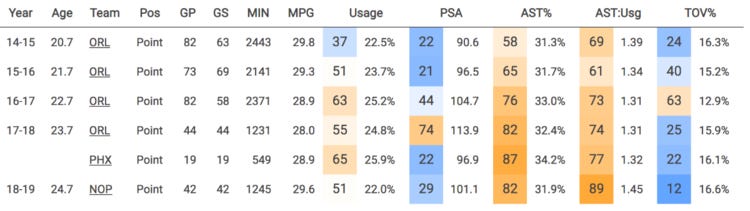

Help may arrive in the form of Elfrid Payton. Payton, one of the many free agent signings for the Knicks after missing on their max stars, offers a more playmaking style of play than DSJ or Mudiay. He has continually improved his assist to usage ratio each season, per Cleaning the Glass, and his numbers imply a higher willingness to look for a pass instead of his shot. The bright orange numbers for AST% and AST:Usg highlight his aptitude as a passer.

Provided he never copies Payton's hairstyle, Knox himself could learn from that example. His slashing style and athleticism allowed him to get to the rim, but once there Knox often found little success. He shot 48% at the rim, a brutal 9th percentile for the league. I felt like he often missed a chance to pass out from the drive and instead committed to shooting regardless. His assist to usage ratio sits at 0.29, a bottom-five percentile; Knox often had a tunnel vision that cost his efficiency and rarely produced for his teammates.

Yet, when he did play out of the drive, his size and vision allowed for easy wins. Look at this beautiful pass to Mitchell Robinson during Knox’s fantastic December, where he ended up winning East Rookie of the Month. Knox used his speed to get to the rim, attack the pick and roll, and flipped up a pass to Robinson once his man moved to cover the drive. To be fair, Mitchell Robinson has the wingspan and flexibility of Doc Ock's robotic limbs, but the instinct to pass out of this drive needs to be empowered.

I’ve purposefully left out any defensive considerations here, as I’m unsure Kawhi or Scottie Pippen could produce on that end for these Knicks. However, just for fun, I pulled some of the lineups stats from Cleaning the Glass and found that Knox played over 200 possessions with Mudiay, Mario Hezonja, DeAndre Jordan, and Daymean Dotson. In those possessions, they allowed the single-worst opponent effective field goal rate in the league, at 65%, and allowed a truly insane 140 points per 100 possessions, or 1.4 per possession.

For context, that is 5 full points worse than what the Golden State Warriors’ best lineup scored on average. Steph Curry shot 52.5% on wide-open threes, per NBA.com, which is 1.575 points per possession; that Knicks lineup's defensive was only slightly more effective than letting the best shooter of all-time take wide open looks.

The Knicks might not contend next year, and after signing the entirety of the power forward market, they might crowd out Knox in what seems to be an attempt at building trade assets for the deadline next season. Yet, as we've seen with the yo-yo reaction to RJ Barrett's start, we cannot let one year of mishaps erase all hope and promise. Knox has a path forward to achieving his offensive potential, and I'm eager to watch him and RJ learn and grow together.

Just, please, let the young guys learn in peace.